Power Failure: The Biggest Business Challenge No One Is Talking About

Adding to his concerns about the global agricultural economy, steel availability, labor rates and climate change, now Titan International CEO Paul Reitz has something new to worry about: electricity. “We’ve had more grid issues in the last 12 months than in the 10 years before that,” says the CEO of the $2 billion manufacturer of heavy-duty wheels and tires based in West Chicago, Illinois. “We’re talking about in the American Midwest, where five years ago, you wouldn’t have anticipated that—maybe in Brazil, China, Turkey and other places we’ve expanded. But those countries haven’t had these issues.”

Reitz operates large industrial presses where he can’t just rely on green alternatives for substantial electricity demand at his half-dozen U.S. plants. “If a press stalls in the middle, it’s dangerous,” he says. “And when the power goes out, you have a lot of scrap product.”

He’s hardly alone. In industry after industry, experts and executives are growing increasingly concerned about the ability of the U.S. to maintain a functional electrical grid in the face of demands it has never faced before. The artificial intelligence boom has tech companies throwing up massive new electron-sapping data centers. The electric vehicle revolution is bringing its own power-thirsty needs in the form of battery factories and vehicle chargers. Throw in the nascent explosion of domestic chip-making, the accelerated reshoring of other manufacturing operations and other new and growing demands, and there are big questions about what happens next.

Can the grid keep up? Probably not. It’s already way behind, with little prospect of gaining ground anytime soon. “We don’t even have a grid that can meet today’s needs, much less the needs of the future,” says Linda Apsey, CEO of ITC Transmission, a transmission-grid operator in the Midwest.

The grid’s challenges aren’t just a matter of capacity but also of reliability, outright fragility and mis-coordination amid crises by utilities, other power suppliers, government agencies and customers. Meanwhile, power is getting dramatically more costly: National electricity prices rose by more than 14 percent in 2022 over 2021, more than double the overall rate of inflation.

Most recently, add to that supply-chain constraints for conducting cables, wooden poles and the other stuff that actually goes into making and sustaining America’s three regional electricity grids, consisting of 190,000 miles of transmission line and involving 500 companies. There’s now an 18-month wait for new transformers, says the International Energy Agency.

“Companies are being forced to think out much longer on big projects, understanding that even once construction starts, it may be 24 or 30 months before they have the power to serve that facility,” says Larry Gigerich, managing director of Ginovus consultants and president of the U.S. Site Selectors Guild. “What does that do from an operations standpoint?”

Historically, the nation’s utility industry has responded well to rising demand. Over the last half-century or so, utilities expanded power generation and availability—through construction of plants powered by fossil fuels and nuclear energy—enough to cover the post-World War II economic boom, the electrification of the American home via the democratization of appliances and the growth of the Sun Belt, thanks to widespread air conditioning. Following that, utilities and their customers pulled off much of a significant transition from legacy coal-based generation to power from natural gas, which has become cheap and plentiful in the United States.

Historically, the nation’s utility industry has responded well to rising demand. Over the last half-century or so, utilities expanded power generation and availability—through construction of plants powered by fossil fuels and nuclear energy—enough to cover the post-World War II economic boom, the electrification of the American home via the democratization of appliances and the growth of the Sun Belt, thanks to widespread air conditioning. Following that, utilities and their customers pulled off much of a significant transition from legacy coal-based generation to power from natural gas, which has become cheap and plentiful in the United States.

“There is still work to be done,” says Barbara Humpton, CEO of Siemens USA, the American arm of the German industrial equipment giant. “But we believe the grid can get to the right point, because the technology needed is already available.”

The question now is whether, after roughly stable consumption from the Great Recession through today, utilities can handle forecasted growth of 2 percent to 4 percent a year for the near future and what Accenture consultants predict will be a 40 percent to 50 percent increase in U.S. electricity consumption over the next 30 years.

“Now we want a grid that’s highly reliable, and we want it to be resilient against climate and weather events,” Apsey says. “We want it to be secure and to access the cheapest source of generation, as well as access clean energy resources. And by the way, we now have to have a grid that can accommodate the electrification of our economy.”

Thus, energy availability and security have emerged as key factors in new siting decisions, and Reinhard Fischer is tussling with it in two roles. As vice president of strategy for Volkswagen North America, he was part of the automaker’s recent decision to put its new battery-cell factory in St. Thomas, Ontario, because “95 percent of their energy is hydropower, and they have plenty of it,” he says. Meanwhile, in his job as a board member of Electrify America, Fischer is pushing the “need to look first at locations where power is available” for the company’s EV-charging stations. That’s why, for instance, the Reston, Virginia-based network struck agreements with Walmart and Target Stores to construct charging centers on their premises.

Dennis Cuneo is also on the cutting edge of the challenges of the straining grid. One of the site consultant’s clients plans to put a $4 billion battery plant in the U.S. and sent information about the project to 27 states, receiving back 72 proposed sites. “We quickly got that down to six, because most of the sites couldn’t meet our electricity demands,” he says. “We wanted more than 250 megawatts of power, but a couple of utilities didn’t have the capacity. Utilities were quoting up to 36 months of lead time on the transformers they would need. Our third issue was wanting mostly renewable energy; no one could fulfill that.”

Plants to make modern batteries for electric vehicles and other equipment require as much as 300 megawatts, far more than a typical auto assembly plant—enough electricity to power 200,000 homes. “There aren’t many sites you can go to that can guarantee to meet that load within 18 months,” Cuneo says.

Add to those complications the consequences of the federal Inflation Reduction Act, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and other outpourings of federal largess, offering hundreds of billions of dollars of incentives for construction of power-slaking facilities to undergird the new, electrified economy.

America’s fast-rising demand for data centers is also contributing. That industry’s electricity demand could double in about five years, according to the Electric Power Research Institute. However, “there’s a big constraint on readily available power to operate all these projected AI projects and also keep up with the data needs of Google, Meta and others trying to help consumers keep their phones and all the content on them incredibly fast and efficient,” says Michael Rareshide, a partner at Site Selection Group.

One unsettling harbinger could be what happened in 2022 in Ashburn, Virginia. That’s when Dominion Energy surprised local CEOs and economic development officials by pausing new connections for an exploding number of data centers, which were already consuming 20 percent of the utility’s electricity generation in a three-county region that touches about one-third of the world’s entire online traffic.

Grid debacles in California and Texas added to the furor. The Golden State mis-regulated itself into a corner where EV mandates, management of spark-prone brush around power lines and sky-high costs have crippled the utility industry. Texas’s vaunted economy was nearly brought low by the Great Texas Freeze storm of 2021, which highlighted, among other things, the Lone Star State’s curious overreliance on wind power.

If grid challenges can humble the two largest state economies in the nation, the problem must be considered not only widespread but endemic. Major causes include:

Underinvestment. About half of the nation’s transmission and distribution lines are 20-plus years old, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Utilities “may have the power,” Rareshide says. “They just can’t get it places. They can’t get transmission lines and substations built fast enough.”

Gigerich says the nation has “underinvested in the grid for a very long time. At the same time, the whole notion of transferring over to green energy has been presented largely as a false narrative.”

As part of their largely involuntary push toward green energy, the nation’s utilities have been decommissioning coal-fired plants faster than they’re replacing them with natural gas and green power. “For the last decade or so, the power industry was a bad place to be,” says Brian Baker, CEO of Sentry Equipment, which makes equipment for power plants in Oconomowoc, Wisconsin. “Utilities were grappling with the prospect of green energy, not investing in new plants and not spending a lot of money on the plants that were up and running.”

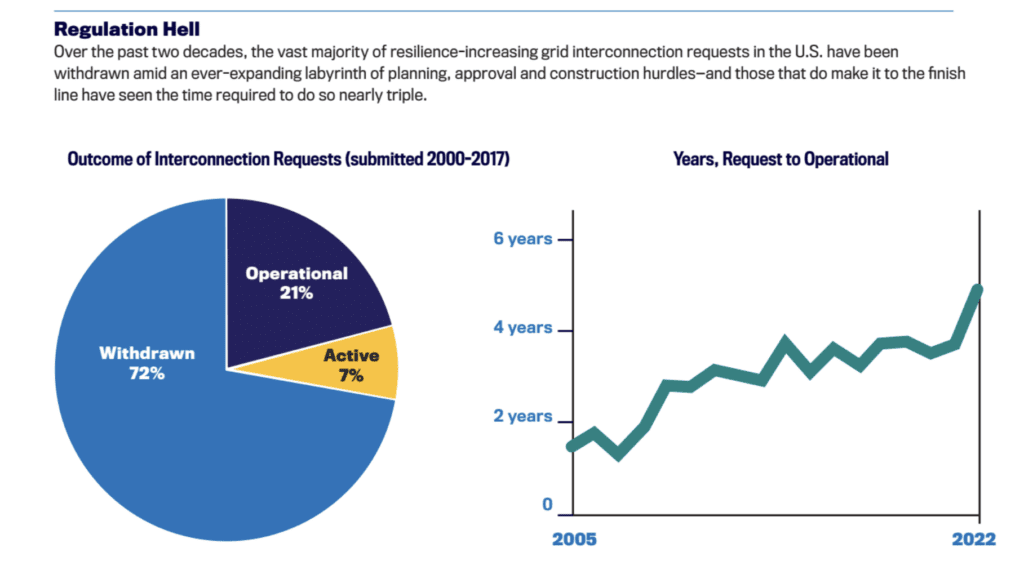

Popular resistance is a factor. “It’s important that we not allow repeated, and what are in many cases meritless, challenges to legal permits,” says Dan Brouillette, CEO of Edison Electric Institute, a utility industry organization. “If we meet very stringent environmental standards, at some point someone has to say enough is enough. It’s a bit too easy to slow things down through regulation.”

Overwhelming demands. Grid operators were awake to the uphill climb they faced but have become overwhelmed by its immediacy. For example, “Today’s level of thirst [by data centers] is a new dynamic that was unforeseen two years ago,” Rareshide says.

Contributors include not just data centers and EV plants but also a broad and accelerating electrification of the hardware that powers the U.S. economy, from heat pumps that are sweeping New England to electric lawn blowers that are transforming the landscaping industry. The bitcoin mining industry has recovered and is contributing to burgeoning electricity demand. So is the oil services business.

Southern’s new projections for Georgia now reflect energy growth of about 6,600 megawatts through 2030, up from its forecast of only about a 400-megawatt increase issued in January 2022. “This is driven primarily by businesses coming to the state that are bringing large electrical demands at both a record scale and velocity,” Adrianne Colins, senior vice president of power delivery for the Atlanta-based utility, said at a recent federal hearing.

Decarbonization mandates. Of the 500 largest companies globally, 63 percent already have set a major climate milestone, according to the President’s National Infrastructure Advisory Council. Such commitments have joined NGO and government pressure to force shutdowns of coal plants and promote resistance, even to the popular alternative of natural gas generation.

Yet about 80 percent of C-Suite leaders across America fear it will take 20 years for their companies to get access to sufficient zero-carbon electricity, according to a recent Accenture survey. A “primary vulnerability [of the grid] is the premature retirement of resources that can provide [conventional] balancing energy and, in the longer term, the risk that there will not be sufficient investment in balancing resources,” said Gordon van Welie, CEO of ISO New England, the region’s transmission grid, at a recent conference.

Meanwhile, solar and wind power, of course, are interruptible. Green energy installations are also typically remote from population centers, meaning they require long transmission lines and tens of thousands of extra transformers to reach customers.

Permitting of these projects “has been slowed dramatically by bottlenecks,” says Scott Tinkler, head of Accenture’s utility practice. “There is as much or more solar and wind capacity looking to connect through the grid as there is capacity online already.” And plans for the most high-profile wind power project in America—Danish company Orsted America’s windmill hub off the coast of New Jersey—have crumbled into a debacle.

Climate change. Some blame climate change for rising incidences of calamities like hurricanes and wildfires. “Climate risk has moved from a decades-forward point for awareness to a near-term consideration in many companies’ risk-management procedures,” said NAIC. Climate change also “makes the task of establishing a reliable and resilient grid that much more difficult.”

Such effects of warmer temperatures “may have a significant impact on good locations for manufacturing in the not-too-distant future,” warns Siemens’ Humpton.

Security threats. They range from outright attacks on electrical substations to cybercrimes. “We need to initiate very secure cybersecurity in our power and other critical infrastructure, such as water, to prevent malicious attacks that could bring manufacturing and other human activities down,” says Tom Coughlin, president-elect of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

Industry, utilities, government agencies, NGOs and others have been addressing the problem of ensuring an adequate grid by dramatically bolstering investments. ITC and regional partners, for example, committed $10 billion to making grid upgrades over the next five years.

Entergy has already replaced about 21,000 distribution poles, placed nearly 1,500 new transmission structures and completed 15 new substations in just the first three quarters of 2023. The moves were part of a 10-year capital expenditure blitzkrieg for the New Orleans-based regional electric utility that involves $16 billion in spending on hardening and improving its systems.

There’s also a growing chorus to give nuclear power another chance. After long providing about 20 percent of America’s electricity, nuclear declined to about a 17 percent share, burdened by high costs, long construction timelines, plant closures and lingering concerns over decades of headline-grabbing disasters including Three Mile Island, Chernobyl and Fukushima.

Mostly, a rebirth of nuclear electricity generation is seen occurring through so-called “modular” reactors, which are small projects that can be built in remote locations and power-heavy industries. There also are new fuels that are “accident tolerant” and can’t be proliferated dangerously by terrorists. Such initiatives offer some hope that the American electricity grid ultimately will succeed in climbing out of its current hole. “A lot of investments are being made,” says Todd Snitchler, CEO of the Electric Power Supply Association, which represents non-utility power providers. “We’re not waiting for the government to tell us what to do.”

Looking to advance Your company’s energy interests? Some ideas:

Search the sticks. Often, more—and more reliable—power is available in remote locations. “Grid-lock” in large cities is pushing more big tech companies into smaller communities—Google 25 miles south of Dallas to Midlothian, Texas, for instance—than ever before.

Adapt to the status quo. It is much faster to leverage already-existing infrastructure than to ask a utility to bring power—or just more power—to a new location. XCharge North America’s EV chargers appeal to commercial customers because they work on current that’s already available. “Nearly all U.S. commercial sites already have 208-volt current, and our units work on either 208 or 480,” says Aatish Patel, president and co-founder.

Understand utilities’ needs. Power providers will be more apt to listen to your concerns if you can help them with things like green-energy generation or green storage, or work with other partners in the area who are already developing a project with the utility, says VW’s Reinhard Fischer. Says Edison Electric Institute’s Dan Brouillette: “Start talking with your utility today about expansion plans, and not just about transmission systems. You may need an upgrade in transmission but also in your distribution system.”

Get on the gravy train. There’s still time to apply for federal incentives that back green-power installations, but expect a logjam. All the federal goodies coming at once “has compressed all the demand for battery plants,” for instance, says site consultant Dennis Cuneo. But “you want to build them now, because you want to take advantage of” government money.

Raise awareness. The public seems to pay attention to grid challenges only when there’s a huge blackout. CEOs must work with “policymakers and regulators to drive utilities to do what’s necessary, to clearly explain to the public the challenges and what the solutions can be,” says Greg Reimer, president and CEO of Surge Battery Metals, which is developing a lithium mine in Nevada. One example: how business leaders including Elon Musk and OpenAI’s Sam Altman have been calling for a national return to nuclear power, which they regard as green—and safe.

Do it yourself. Do what you can to make operations more energy-efficient and lowest-cost, including using new digital modeling. Also, commercial facilities have growing options for generating their own power, including cogeneration, installation of solar arrays and addition of natural-gas generators. Prologis, for instance, has become the third-largest generator of on-site energy in the country by installing solar-powered fleet-vehicle charging platforms at clients’ warehouses. “The best place to charge these trucks is when they’re loading and unloading, and that’s what we’re doing for our customers,” says Susan Uthayakumar, chief energy and sustainability officer for the San Francisco-based logistics giant.

But be careful. “Having grid-scale reliability and access to all sources of generation is going to be cheaper and more reliable than having your own facility and cutting the cord to the transmission grid,” notes ITC Transmission CEO Linda Apsey.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.