(Dis)Trusting Geopolitical Experts and Models

Given the difficulty of distinguishing wisdom and folly in geopolitical assessment, what are executives and investors to do—or avoid doing? Powerlessness can chafe boardroom mentalities and tempt leaders to outsource geopolitical assessment to expert opinion or to sophisticated data models.

Both have limitations. That makes scenario analysis—in effect supplanting a single plan or point forecast with multiple futures—a valuable and necessary alternative. But leaders should not approach geopolitical analysis like the corporate-strategy function: there is no such thing as a meaningful five-year geopolitical plan. Rather than following the approach used in preparing corporate strategies, we see geopolitical risk assessment as being closer in style to the role played by the CFO. It requires the ability to react, quickly assess impacts, and disseminate directional guidance to organizations. For that, leaders must enable their organizations to build the skill and muscle memory necessary to execute bite-sized, small-macro impact analyses ongoingly—rather than invest in an assessment of grand geopolitical strategy.

As leaders try to get ahead of geopolitics, they are often offered two shortcuts to reading the future. On the qualitative side, great trust is often placed in experts, frequently past practitioners of statecraft who were in the room. On the quantitative side, a growing number of approaches for measuring and modeling geopolitics are on offer. We think leaders want to be careful with each.

Assessing the risk of war hasn’t gotten easier. In Geopolitical Alpha, a 2020 book promising investors a “framework for predicting the future,” the author, a geopolitical analyst in an advisory firm, offered up an analytical framework of “constraints.” Illustrating the constraints on geopolitical ambitions and conflict, he called the idea that Vladimir Putin would attempt to recreate the Russian empire by force “flawed.” Specifically, Russia’s “symbiotic relationship with Europe is a major constraint…it is actually Berlin that has Russia by the…pipelines.” Thus, invading Ukraine could never happen because it “would be economic suicide to turn off the tap to Europe.” Sadly, none of that analysis and resulting prediction have held up.

Of course, geopolitical experts also make prescient calls. But even then, the limitations are striking. Consider George Kennan, who penned one of the most prescient geopolitical predictions on record. In his famous “The Sources of Soviet Conduct,” published in Foreign Affairs under the pseudonym “X,” Kennan wrote that “Soviet power…bears within it the seeds of its own decay, and that the sprouting of these seeds is well advanced.” But he published the article in 1947. If the seeds were “well advanced,” placing the Soviet Union perhaps in the second half of its lifecycle, why then did it take over 40 years for his prediction to come true?

As Kennan’s accurate, if not timely, analysis reminds us, forecasts have a time component that pulls analysts to shakier ground. By focusing on the foundational weakness of the Soviet Union rather than on strict time horizons, Kennan was able to produce valuable insight. Yet experts are often rewarded for boldness and precision. These rewards encourage confirmation bias and the ability to rationalize former misses—each feeding into overconfidence. In 1988, academic Philip Tetlock asked an august panel, including Nobel laureates, to forecast five years into the future. Questions included whether they thought the Soviet Communist Party would remain in power. The experts who assigned confidence of 80 percent or higher to their answers were correct only 45 percent of the time.

We do not wish to argue that there is no value in leveraging geopolitical experts. On the contrary, real insight often comes from those who professionally analyze geopolitics and from former practitioners who provide perspective and historical context. The problem comes when executives expect the impossible and try to buy the future. Experts cannot consistently make accurate geopolitical calls, much as economists can’t get it right consistently. Their genuine insight must be used with that in mind.

Geopolitical quantification, the other tempting tool for taming geopolitical risk, stems from the allure of models, indexes, and dashboards. These have the scientific veneer of command and control. As management scholar Peter Drucker argued, “What gets measured gets managed—even when it’s pointless to measure and manage it, and even if it harms the purpose of the organization to do so.” This pertains to internal corporate dynamics, but it can also pertain to external risks.

The desire to quantify has led in recent years to the emergence of indexes that purport to measure geopolitical stress and risk. Perhaps in keeping with a general societal thrust toward quantification, the numerical expression of risk should, in theory, allow decision makers to compress complexity into inputs that can be used in decision-making. And because these indexes measure and weigh linguistic signals in public discourse in near real time, they are both timely and avoid anchoring on any specific expert.

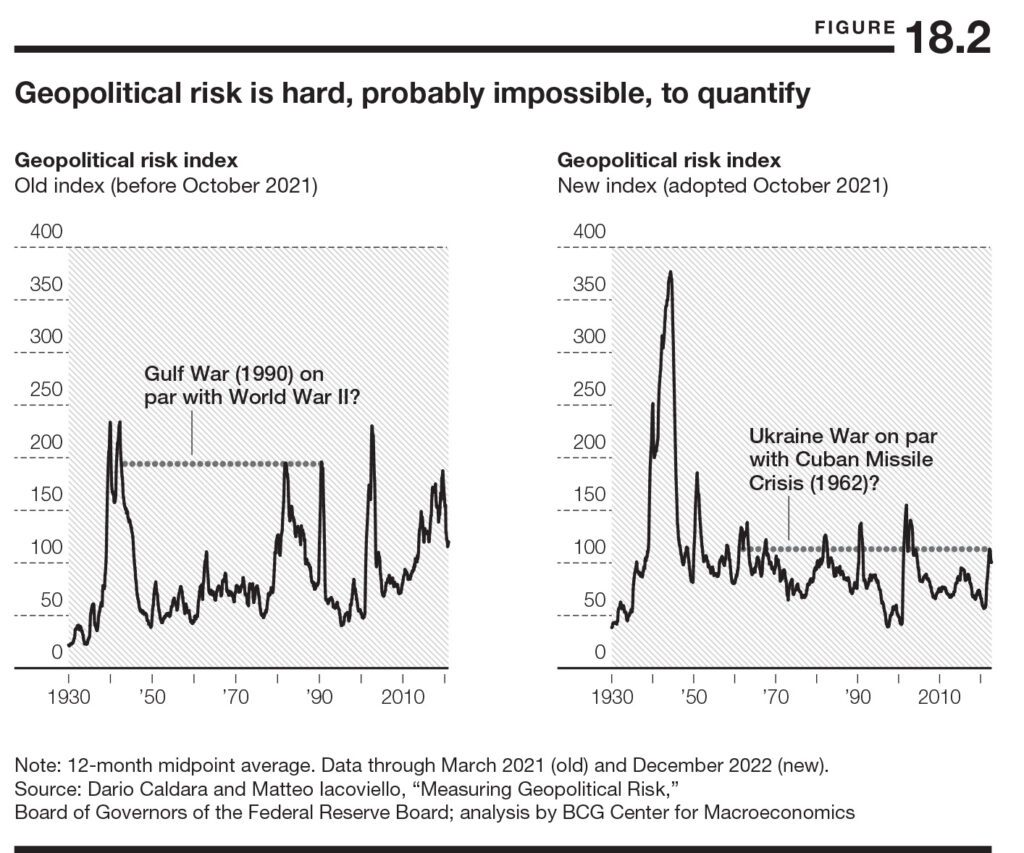

But such indexes suffer from significant shortcomings. Consider figure 18.2, which charts levels of risk via a geopolitical risk index that was created by researchers at the Federal Reserve and that was in use until late 2021. While the time series seems to capture moments of known stress—World War II, 9/11 and others show up as spikes—these prints are not realistic on a relative basis. Would anyone believe that the geopolitical stress of the Gulf War, 1990–1991, was anywhere near that of the Second World War?

Yet quants are always looking to improve their methodology as seen on the right-hand side of figure 18.2. The Fed’s new-and-improved index has shifted into something more superficially sensible—World War II now towers over everything else. But can one meaningfully say that the Ukraine War that began in 2022 prompted the same uncertainty as the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, when the United States and the Soviet Union came close to nuclear annihilation? Sure, comparing the two could result in prolonged debate—but that only proves the point. It is unsatisfying to equate the complexity of these two episodes with the flatness of a single number. The false equivalence exposes the weakness of quantitative approaches to geopolitical risk management.

As with expert opinion, it is not that quantification itself is fatally flawed; the hazard lies in how the quantification is used. With experts, the danger is overconfidence; with quantification, it’s oversimplification. It is worth remembering the adage that what counts can’t always be counted—and what can be counted doesn’t always count.

Reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review Press. Adapted from SHOCKS, CRISES, AND FALSE ALARMS: How to Assess True Macroeconomic Risk by Philipp Carlsson-Szlezak and Paul Swartz. Copyright 2024 The Boston Consulting Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.