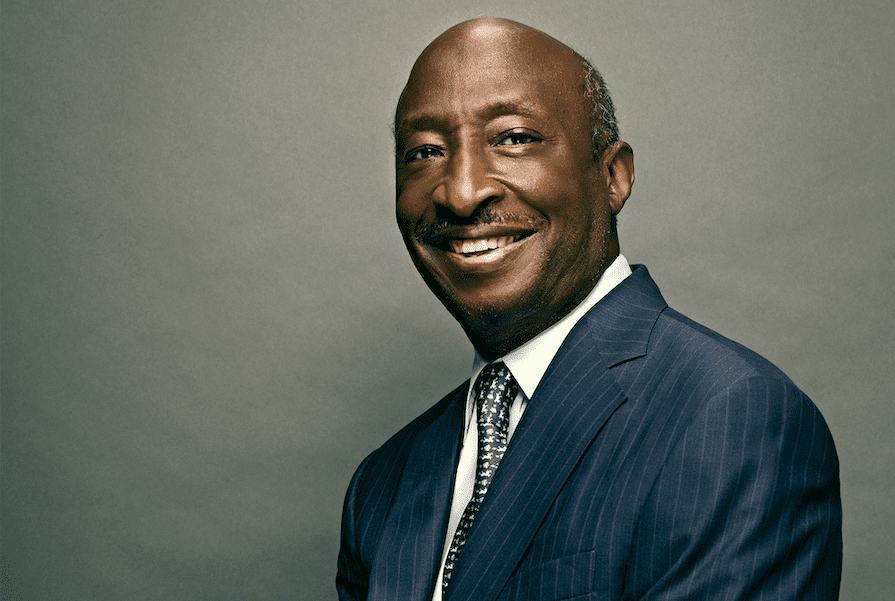

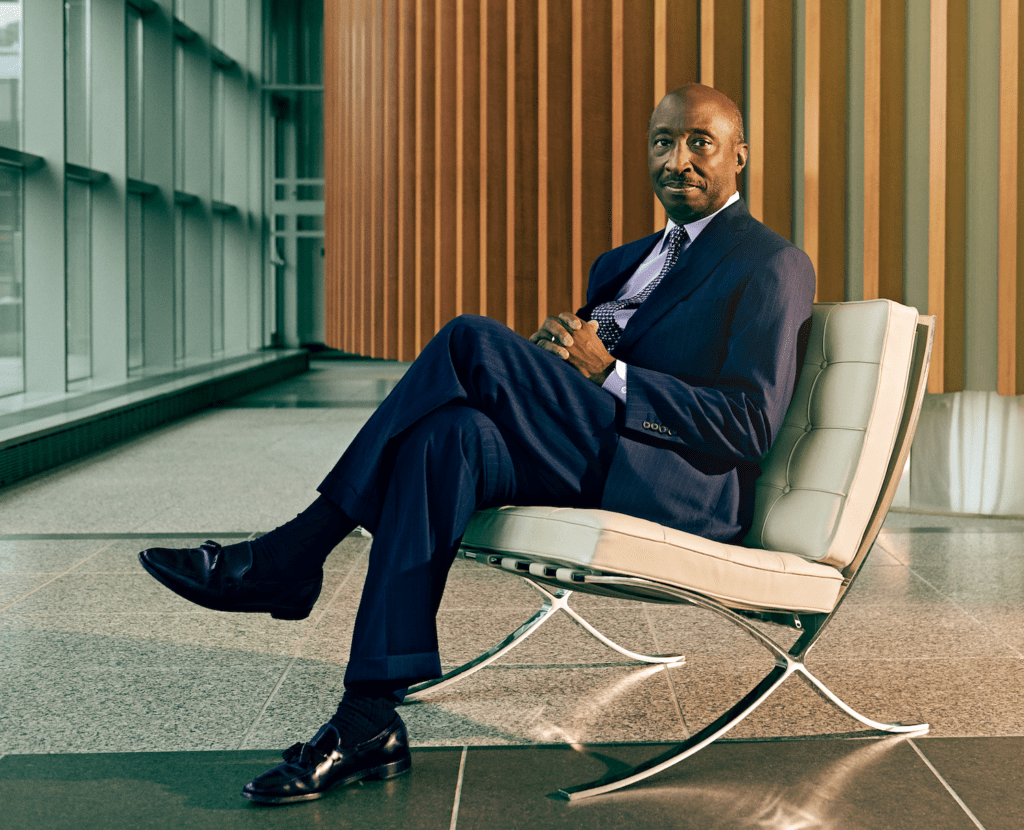

2021 CEO of the Year: Inside Ken Frazier’s Long Game

Go into Ken Frazier’s office—his new office, a far smaller one since he took on the role of executive chairman following a decade in the CEO chair at Merck—and he’ll show you the photos. Six in all: his son, his wife, his daughter, one with him and former President Barack Obama, one with Warren Buffett and one with Pope Francis.

Go into Ken Frazier’s office—his new office, a far smaller one since he took on the role of executive chairman following a decade in the CEO chair at Merck—and he’ll show you the photos. Six in all: his son, his wife, his daughter, one with him and former President Barack Obama, one with Warren Buffett and one with Pope Francis.

The Pope may seem an outlier, but Frazier, who turns 67 in December, says they actually had a lot to talk about when they met in 2017. The Pontiff is a chemist by background and used Merck reference books. He used the session to lobby Frazier. “He wanted to encourage Merck to do more for people in the world who were suffering,” says Frazier. “His comment was essentially: ‘The distinction between saints and sinners is less actionable because we’re all sinners.’ He said, ‘We have to think about the distinction between the rational and the irrational,’ which I thought was an interesting thing to hear from a Pope, right? And he sent me off on my way, saying, ‘Can you do more for our brothers and sisters who are suffering around the world?’”

That Papal “ask” encapsulates life as CEO of one of the world’s largest drugmakers. Yes, of course it’s about commerce, but, as anyone who’s ever had a sick parent, kid or spouse knows, it’s also about a whole lot more. Being a big pharma CEO requires nailing this balancing act—societal needs and shareholder needs—like few other jobs in business. And Frazier has handled it brilliantly, becoming perhaps the most influential example yet for a school of business leadership that sees corporations—and CEOs—as cornerstones of democratic capitalism, as stewards of society.

“Ken is a remarkable leader with the vision and determination to do what’s right for society while delivering long-term value for shareholders,” says Bank of America’s Brian Moynihan, our 2020 CEO of the Year, who was a member of the selection committee that named Frazier 2021 CEO of the Year. “His leadership at a time when society needed him most has been exemplary. “

Tamara L. Lundgren, CEO of Schnitzer Steel Industries, also on the committee, agrees. “He has been an inspired and inspiring leader—delivering excellent results, continually innovating and providing an impactful voice on critical issues that affect our country and the business community.”

During his decade leading Merck, Frazier resuscitated the company—arguably saved it—from drifting into expiring patents and increasingly lackluster results. Recruiting top talent like R&D chief Roger Perlmutter, whom he lured back to Merck in 2013 after 11 years at Amgen, he reinvigorated the product portfolio and fattened the development pipeline, ensuring that the storied company George Merck founded in 1891 remained competitive—and growing (Perlmutter retired in 2020). Under Frazier, Merck remained committed to R&D (against prevailing trends at first), developing vaccines for Ebola, pneumococcal disease and human papillomavirus while also continuing to the fight against HIV. And although the company missed on developing a vaccine for Covid-19, in late September Merck announced the first effective antiviral pill for the disease, which could offer a powerful new weapon in the global fight against the pandemic.

But what will likely be the biggest legacy of the Frazier era is the blockbuster cancer drug Keytruda.

The basic research that led to Keytruda arrived at Merck in 2009 as part of the $41.1 billion takeover of Schering-Plough. It relies on humanized antibodies rather than chemotherapy to attack cancer cells. Seven years after being approved for a narrow range of targets, it is now one of the most successful cancer treatments ever, saving—and extending—hundreds of thousands of lives. Worldwide sales of Keytruda grew 30 percent to $14.4 billion in 2020 alone (the company’s total sales were $48 billion last year),making Merck one of the world’s leading players in cancer treatment and helping to usher in the age of immuno-oncology. Under Frazier, Merck’s stock price more than doubled.

Not bad for a lawyer-turned-CEO from working-class Philadelphia. His father was a janitor with sparse formal education. Frazier credits the school busing movement of the 1960s for giving him access to more rigorous schools than those available in his neighborhood. After attending Penn State and Harvard Law, he spent his early career at Drinker Biddle & Reath in his hometown, where, in addition to corporate work, he overturned the sentence of a man falsely convicted of murder after he’d served 19 years on death row.

He was lured to Merck, then a client, in 1992 by the company’s legendary CEO, P. Roy Vagelos (Chief Executive’s CEO of the Year in 1992). Later, as GC, Frazier defended the drugmaker against lawsuits alleging that its anti-inflammatory drug Vioxx caused strokes and heart attacks. Rather than immediately fold, Frazier opted to fight. The company eventually settled in 2007 for less than $5 billion, a small fraction of the $50 billion some predicted. The victory assured a future for Merck—and marked Frazier for the top job. After a variety of stretch assignments, he became CEO in January 2011, serving until this July.

He was lured to Merck, then a client, in 1992 by the company’s legendary CEO, P. Roy Vagelos (Chief Executive’s CEO of the Year in 1992). Later, as GC, Frazier defended the drugmaker against lawsuits alleging that its anti-inflammatory drug Vioxx caused strokes and heart attacks. Rather than immediately fold, Frazier opted to fight. The company eventually settled in 2007 for less than $5 billion, a small fraction of the $50 billion some predicted. The victory assured a future for Merck—and marked Frazier for the top job. After a variety of stretch assignments, he became CEO in January 2011, serving until this July.

Along the way, he’s had his share of well-known controversies. As lead director at Exxon, Frazier spent the early summer in a headline-grabbing proxy brawl with a tiny activist hedge fund, ostensibly over issues related to environmental sustainability. Exxon lost. In 2017, he famously quit President Donald Trump’s American Manufacturing Council in the wake of Trump’s comments about the racial violence in Charlottesville, Virginia. In 2020, he took up the fight for voter rights following Trump’s defeat.

“Sometimes the issues call you,” he says of his decision after Charlottesville. “I didn’t feel like I woke up one morning and said, ‘I want to resign from the president’s manufacturing council and create a difficult situation with the President of the United States.’”

But in speaking out on the issues he believes in—from voter access to racial discrimination to criticizing his own industry over drug pricing—Frazier has shown himself to be unafraid to say and do what he thinks is right, even if it some find it divisive. “People are unhappy with you, you get criticized, but I don’t think you can do anything important if you’re not willing to take a stand and be criticized,” he says. “I just don’t think you can do anything important.”

That clear-eyed courage, coupled with principled leadership and long-term transformational success, led our CEO of the Year Selection Committee to name Frazier 2021 CEO of the Year. “Ken Frazier has delivered impressive results as CEO,” said Carmine Di Sibio, the CEO of EY and a member of the committee. “He’s done this by focusing on his people, his shareholders and his community. Ken is a true leader and trailblazer demonstrating the courage and generosity needed in our world today.” In April and August, Chief Executive sat down to talk with Frazier. The conversations were edited for length and clarity.

The important thing about leadership, and it’s particularly true during periods of uncertainty and disruption, is to be anchored around principle. If your leadership is stemming around a series of values and principles, no matter which way the wind blows, you feel like you have much more of a solid foundation for the decisions that you’re making. Our business is one of innovation. Our business model is one where we have to reinvent our company every 10 years because patents run out. And if we don’t figure out how to reinvent ourselves, we’re out of business.

So, disruption is fundamental to a scientific model. There will always be new science, new ways of doing things. What’s really changed in the last few years is the amount of disruption around us. The pandemic is a classic example. This company was doing extremely well and then the pandemic hit. It was disruptive to our business because 70 percent of our vaccines and medicines are dispensed through the health system. When the health system was operating at a fraction of its capacity, it affected our business because no one was going to take their child to get a Gardasil shot, right? People weren’t getting elective surgeries.

One of the most important things for us was to ensure the consistency of our supply of our medicines to patients both in clinical trials and in the actual world. On the reliability of our supply, there’s a measure called line-item fill rate, or the number of orders that are filled completely the first time, that went up after the pandemic. Even with people’s children being at home and everything else, our ability to meet patient demand post-pandemic or in the midst of the pandemic was greater. I can only attribute that to the values.

One of the things I’m most proud of is that from the time I became CEO, 25 days into the job, I withdrew the long-term guidance that was out there. There were three years left in the long-term guidance. So, 25 days into the job, I called my board up and said, “This guidance requires rather substantial, and, I thought, indiscriminate cuts in the R&D budget. And once I do that, I cannot stand up and say, ‘Merck is about science.’”

There was a period of time in this industry, I would say from the early 2010s, where you saw companies following an approach to the business where they reduced their research budgets. I have now grown my research budget to be the second-highest in the industry. I tried to show that through consistent capital allocation, that those are the kinds of things that we’re going to focus on as an organization. Putting your money where your mouth is as it relates to scientific investment.

[George Merck, the former] CEO of Merck, was on the cover of Time magazine in 1952 because he made a speech at the Medical College of Virginia, where he said medicine is for the people, not for the profits. The more we’ve remembered that, the more profits followed. Now I tell my kids that being on the cover of Time in 1952 was like being on every social media page at one time, for a whole week. Merck was a pretty obscure company, but Time thought the idea was important enough to put on the cover. Every Merck employee knows that. At the end of the day, they’re interested in whether or not those values are being clearly reflected in the decisions and actions that I take as Merck’s CEO.

It helps to come up in a company where you’re preceded by people like Roy Vagelos, who would say to me, for example, “There are only two metrics that the CEO of Merck really is judged by: one is how many people you help and the second is how much help you give those people.” If you apprenticed with the kind of people who’ve always put those values first, you know that that’s what your job is.

It’s not easy in a sense that we all want to be liked and respected, and you don’t want to read analyst reports saying that you’re a bad CEO. On the other hand, it was never ultimately hard because I knew I was here to serve a higher purpose, that the company was here for a higher purpose. This company is more than a vehicle for the creation of shareholder wealth. That’s not fundamentally what it is. It is fundamentally a vehicle for improving and sustaining health around the world. And when we do that effectively, we create a more than fair return for our shareholders, but you have to understand what’s the driver and what’s the lagging indicator here.

This whole shareholder TSR thing is a real problem because it’s not a year-in-and-year-out reliable way of measuring your company. How many important new drugs you bring over decades is a reliable way of measuring how well your company is functioning. Sometimes the street will be irrationally in favor of your company, and sometimes it’s not.

For the CEO of a company like Merck, the most important thing is the general direction of the company. We’re going to be an R&D company. We’ll never cut back on R&D. With R&D, you have to understand this is a very different industry when it comes to allocating capital. More than 90 percent of things we actually think are good-enough ideas to invest in turn out to not be good ideas. They either don’t work or they don’t work better than what’s already on the market. So, we’ll fail more than 90 percent of the time. Our strategy comes down to focusing on the science.

Then the second thing is ensuring that we have the scientific talent that can have the right kinds of insights to make the right choices as to which to move forward. The CEO of Merck can’t really drive the most important strategic decisions that happen inside the company. My job is to create an environment where I say science is what we’re all about. It’s what we invest in. It’s what we value. And we’ll hire the best scientists and create an environment where they can do what they’re going to do. Many of our best scientists have worked 40 years, and nothing [they developed] has worked.

The product development cycle is extremely long in this business. We say 12 to 15 years to develop a product, but that doesn’t count all the early years of scientific inquiry that lead to this, right? So, at my level, the question is, how much of our capital will we allocate to new scientific discovery? One of the things I’m most proud of is building three new discovery hubs in the last few years, in south San Francisco, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London. The strategy is to invest in those kinds of opportunities for us to look at cutting-edge science and to hire the right people.

If you’d asked me when I was the new CEO, “Couldn’t Merck possibly be the leader in cancer?” I might have had no way of knowing that. But deep in the bowels of the company those two guys [were] working on immuno-oncology. And then we bring in Roger Perlmutter who happens to be a person who spent a lot of his life in oncology and is an immunologist by training. He recognizes the asset. He comes to me and he says, “This is worth putting all our resources behind because this is a once-in-a-generation product.”

As the CEO of Merck—I just want to be clear—my level of strategy is to enable good science. That is the strategy. And then you have to trust that that science is going to turn into things that are going to make a difference in the world. It’s talent, and it’s placing bets and celebrating the importance of doing good science.

That was very hard psychologically for this company. First of all, Merck was one of the early investors in mRNA technology, and we had a very large investment in Moderna. When Covid came along, this company had deep experience with replicating virus-vector vaccines. We have been successful most recently in a compressed timeframe in Ebola with that approach. Most companies try to see how the things they understood might be applicable to this. Our goal, when we set out, was to develop a vaccine. It was a high goal: We wanted a single-dose vaccine. We wanted long-term durability. You probably see that we need booster after booster after booster—which is better than not having a vaccine—but our goal was not to have that situation and to have a vaccine that was broadly protective, because when you challenge viruses, they tend to mutate.

At the very beginning, we took advantage of platforms that had been useful for us in the past, one that worked in Ebola, another that works in the measles context. And the question was, could we develop a vaccine that had the characteristics that I just talked about? The vaccines did not produce the level of immunogenicity that we had hoped for. But again, that goes back to what I said: You do good science, and it doesn’t promise to pay off. While all of us would want to have seen Merck be a leader in vaccine development, those vaccines didn’t work.

So now the question was, how do we contribute? We decided to help J&J manufacture their vaccine. By the way, we’re continuing to do some work in the vaccine area, and we’re developing an antiviral, which I think the world now sees it will need because while these vaccines are important vaccines, they’re not going to be distributed all over the world because of the cold chain. Just think about in the U.S. how few people are really going to take three doses of the vaccine.

It was a disappointment but a leader needs to help people keep their heads high because our business is fundamentally about failure. This just happens to be a very visible failure, but fundamentally, it is what our business is ultimately about. So, when talking to our colleagues, it’s maybe not celebrating the failure, but reminding them that that’s the business that we’re in, and that while we were unsuccessful in this situation, that doesn’t change our commitment to actually develop something really important. In other words, you can’t hang your head.

This is a great thing to be CEO of the Year, but I’d trade it in a New York minute for a vaccine. At the same time, I’m pleased that Moderna, Pfizer, BioNTech and J&J were successful.

One of the things that I’ve stressed from the time that I became a CEO is that I don’t believe in top-down management. I believe we should invert the pyramid because the CEO is the farthest person from the customer, the farthest person from the research bench, the farthest person from the manufacturing interface. I’ve tried to be very clear to my direct reports and their direct reports that the old-fashioned hierarchy that was corporate management is not at all appropriate for the kind of fast-changing, volatile world in which we operate.

I say it this way: If I could do one thing at Merck, and one thing only, it would be to convince smart people that they already know the answer and that they don’t have to turn to senior management to learn the answer.

Keytruda is a great example of that. When I had a chance to meet the two young scientists who began working on Keytruda, they wanted me to know that their boss didn’t believe in immuno-oncology. So they continued to work without telling their boss. Even when the boss kept saying, “Stop, stop, stop,” they said no.

I said, “What encouraged you to work on this, despite the fact that your boss didn’t want you to work on it?” And they said, “Because our boss is really a portfolio manager, not a real scientist. We understood the science here. So, we knew we were onto something.”

I like to repeat stories like that. I say to people, imagine that those two young scientists had accepted the culture of many corporations, which is: You don’t piss off your boss. Imagine how many cancer patients would not have been helped, would not have been cured.

The scientists tend to like cognitive leaders. The salespeople tend to like more emotion-based, more inspirational people. As a CEO, you have to lead both. You have to lead from a cognitive standpoint, you have to lead from an emotional or inspirational standpoint. You also have to lead from a moral standpoint. You can’t negotiate on integrity.

The second thing is, obviously, they have to manifest the grasp of their area, right? The leader in our research organization has to be a world-class scientist, right? It is non-negotiable, right? Because everybody in that organization wants to know that their leader is a world-class scientist.

Then the third thing they have to manifest is their own concern for people because, at the end of the day, this job is less about managing workflows and more about leading people and developing people. You get the stretch opportunities, those kinds of things.

The other thing we haven’t talked about is the importance of diversity and inclusion, creating an inclusive environment where all people can be successful and contribute.

Well, I have a problem with cultures where the fit is narrow. What you want is an environment where lots of different people who come from different backgrounds and have different personalities can contribute. I understand the “fit” word, but I always react negatively to it because the worst thing that you can do is have a narrow culture and groupthink inside your company. Those are enemies of innovation.

What it comes down to is choosing your leaders carefully and watching how those leaders lead. The culture is the leaders. You can say: “I want a culture of inclusion,” but if you pick leaders who don’t value inclusion, those are just words on a piece of paper. You can say: “I believe in empowerment,” but if you pick leaders who keep all the power and make all the decisions, then saying you value empowerment doesn’t matter. The culture is the behavior in the mindset of your leaders.

It wasn’t easy to [resign from the President’s manufacturing council]. But again, it comes down to your principles. For me, in that one instance, it was a question of, do you really take a stand for your principles?

And with George Floyd, when you’re a Black CEO and the business community is asking the question of what we should be doing in order to create more opportunity for people who have been excluded, it was my obligation to speak out to people and help them understand the opportunity that business has to close the gaps that exist in our society, the incomes, the gaps, the racial injustices in our society. I’m a big believer that business has that role and can adopt that role.

I don’t want to be too autobiographical, but I feel extremely fortunate to be an African-American born in the inner city at the time I was. Both John Locke and Warren Buffett talk about what they call the random lottery of birth. My younger sister and I, the eighth and ninth of my father’s children, came along at a time when social engineers decided to take a few Black kids out of the so-called ghetto and put them on buses and give them educations. There’s no question in my mind that I was given opportunities not made available for everybody in society. In Hamilton, there’s the comment about “being in the room where it happens.” Being one of three or four African-Americans who happens to have a place in that room, I do feel a responsibility to speak for the people who are marginalized in our society.

Sure, my job always was to run this company well, to make my margins, to compete for customers, to drive profit, to drive growth. But it’s also the case that if this company is going to be successful—or any company is going to be successful—it’s got to be successful in the context of a society that is successful.

We live in an interdependent and interconnected world. If patients can’t afford medicines, if people can’t find their way into the middle class, how can our companies thrive when the people around us are not thriving? If we’re not able to develop people in this country to do the jobs that we have—and there are about 10 million vacant jobs in the U.S.—how can we hire people? We’ve got a lot of people for whom there’s no access to the middle class.

So, for me, as a Black CEO, it was important for me to speak to the disparities and opportunity that exist in this country. Fundamentally, what makes the U.S. different from other countries is the role of business—that is to say, the private sector, talent, its resources, its infrastructure—to help reinvent our society.

We have more than 50 companies in OneTen now, and we’ve evaluated our job requisitions, and 80 percent or 90 percent of the jobs require a four-year degree. Almost 80 percent of African-Americans do not have a four-year degree. So, the question becomes—particularly in the context of 10 million jobs that are not filled—what would the world be like if we based opportunity on skills, not on credentials? What we’ve done is we’ve got 56 leading companies to agree to look at their own internal hiring criteria and to really ask whether or not a job requires a four-year degree.

My son is a great kid. We spent $300,000 sending him to college. He has a degree in political science. Now he’s in New York selling luxury real estate. So, what does he have to do? He goes to a big Manhattan real estate firm. He’s an apprentice. He has to get a real estate license. He has to trade on a set of skills. And it’s not relevant at all that he has this four-year degree in political science from Lehigh University.

What we want to be able to do through OneTen is to create a pathway or access from the inner city or from rural America to the middle class. To me, this whole issue of having more people in the middle class—all of our companies are going to benefit from that.

My dad had a third-grade education. He was a janitor, but he had dignity. Like I sometimes say—and I hope this doesn’t sound corny—I followed my father into the bathroom early in the morning, so I could catch the school bus and go across Philadelphia to, frankly, White schools, which were rigorous. One of my enduring childhood memories was the smell of my father’s shaving cream. That gave me a perspective of what it meant to be a person who actually could hold his head up high. Too many Americans can’t do that. They don’t know where their next meal is coming from. They have housing insecurity, and I think business can do a lot to align society’s needs with our own needs.

I’ve often said when I spoke on this issue that if you look at this country, we tend to live in enclaves of people who are like us. Unfortunately, our public schools are more segregated now than they’ve, frankly, ever been. We go to church, synagogue and mosque with people who are like us. We consume media, social media and other media [the same way]. If you’re not in the armed forces, the workplace is the last place in America where you can’t choose who you associate with, who’s on your team. And it seems to me that if we want to lead to the kind of pluralistic society that we aspire to be, CEOs have that role.

This country is so different from other countries. Many places in this world you’re either born permanently in a class that is privileged or permanently in a class that is disadvantaged. This country doesn’t have that. And a large part of the gateway between poverty and the middle class is business.

I just want to believe that business can solve those societal problems. If we lift our eyes up beyond the immediate balance sheet, we have an opportunity to make a difference.

I am optimistic. Because I believe all of us have agency. As long as we believe in what this country stands for, we can make a difference. And this country has seen good times and bad times. Most Americans believe in the fundamental values of this country. I think that, right now, coming to the role of CEO, when all the opinion surveys show that the public doesn’t trust government, it doesn’t trust religious institutions, business actually has one of the highest reputations in our country, and we are able to solve problems pragmatically. It’s all about CEOs deciding that they are going to lead their companies in a way that not only creates a fair return for their shareholders but creates a fair return for our society. Those two things are not inconsistent.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.