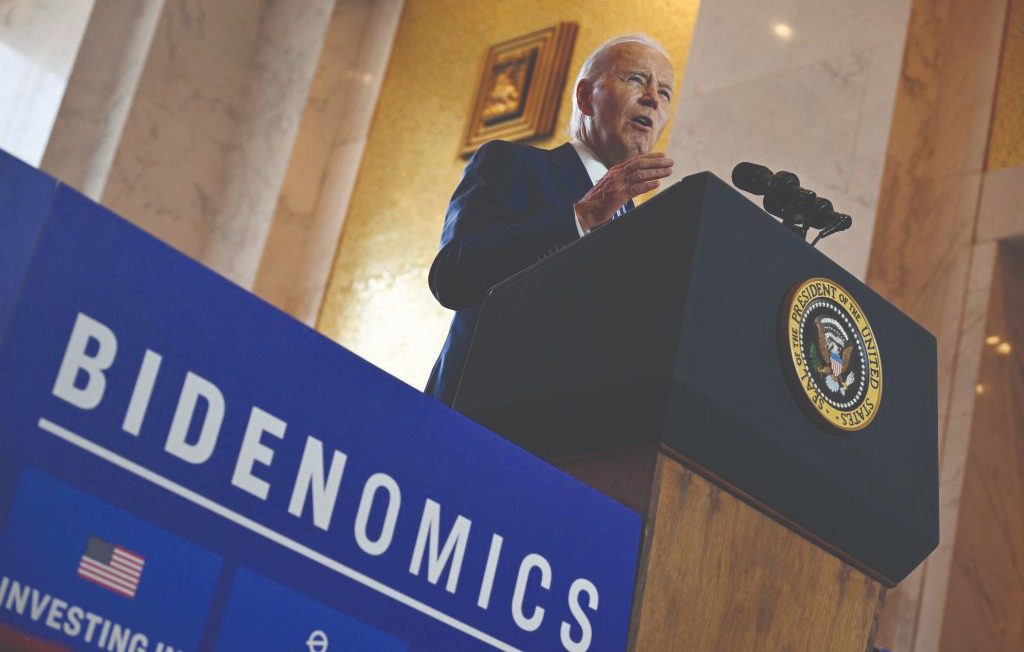

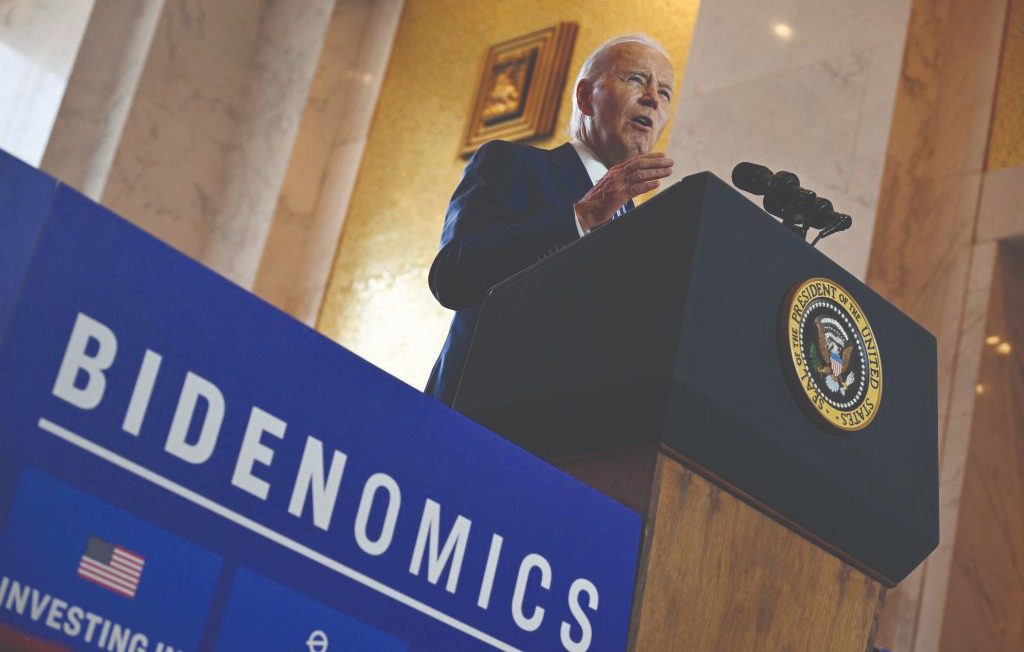

Playing Bidenomics To Win

When it comes to the Biden administration’s new industrial policy, most of the winners—green-energy providers, factory-construction companies, manufacturers of industrial electrical equipment and automakers—are pretty obvious. Then there’s fake meat.

“Potentially, [a] loan program is open to us and will consider cultivated meat and other alternative proteins as part of their program,” says Josh Tetrick, CEO of Eat Just, one of two companies that recently gained U.S. government approval for commercialization of its lab-based faux-chicken products. “We’re learning about how long it takes, processing the probability of success and what we’d need to do internally to make it happen and be successful.”

It’s a great example of the opportunities that abound in the plum orchard of industrial subsities that’s come to be known as Bidenomics. With an estimated $2.4 trillion in federal incentives and matches, the federal government’s most robust guidance of American industry since World War II has something for nearly every CEO willing to look, including multimillion-dollar incentives to “sustainable” food projects whose goals include eliminating the raising of animals for slaughter.

The Biden administration and Congress unleashed a stream of huge financial incentives under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, CHIPS and Science Act and other potential windfalls that are reshaping not only companies and industries but the very structure of the domestic and global economy.

“We saw the value before in doing this, because the world is regionalizing,” says Michael Finelli, chief of North America for Brussels-based chemical giant Solvay, which already had 35 plants in the United States and then decided to build an $850 million plant in Georgia with a partner to make coatings for lithium-ion batteries. “A $178 million grant from the U.S. was the tipping point to make the decision.” Want to play? It’s not too late. Here a few tips for CEOs navigating this brave new world of Washington-born largess:

Find the open spigots. Under new energy-related policy, for instance, companies will continue to qualify for some tax credits regardless of their actual ability to reduce emissions, says Michael Wolf, global economist for Deloitte consultants. “The U.S. policy is all carrots.”

Example: Ford got a $9.2 billion loan from the Energy Department for three battery plants it is building in the South. But there’s been no threat by the Biden administration to rescind those incentives even after Ford’s sales of a pioneering EV, the F-150 Lightning pickup truck, flagged so badly early this year that the company had to cut the vehicle’s $50,000 starting price by a whopping $10,000.

And in the silicon trade, the EU, China and South Korea felt compelled to come up with their own versions of the U.S. CHIPS Act. “This creates an opportunity for companies in sectors related to emissions reduction or semiconductors to benefit from competing subsidies across the globe,” Wolf says.

Command the details. “You always have to make sure you’re following the rules to be eligible for these credits,” says Tony Caleca, managing partner for Armanino consultants. “A lot of validation goes along with that. You have to have systems of control and a rules set so that everything is buttoned up and ready to go when someone asks why you’re eligible for this. Don’t get caught on the back side of not being eligible.”

Asutosh Padhi, managing partner for North America for McKinsey consultants, says that compliance with the terms of new industrial-policy handouts requires “significant and quite sophisticated administrative and monitoring requirements. Leaders need to be prepared for ongoing, detailed reporting of progress and performance.”

Balance is key. “Have a clear understanding of the policy landscape,” says Azaz Faruki, a principal with Kearney consultants. “Then understand how to take advantage to meet the organization’s goals and also tie it back to the long-term vision.”

Padhi says “these incentives are most effective when applied to unlock plans that have been in the works—or at least on the horizon—and now can be accelerated,” such as entering new markets or customer segments where costs and conditions were prohibitive before.

Expect strings. Recipients of the new federal largess “are going to have to perform under the contract, and your commitments of the size of the plant and the time frame and jobs and a DEI component,” Finelli notes. “And the government retains a reversionary interest in the assets they’re paying for, so you’re not as free to do with the plant what you would have done if you’d done it yourself.”

Plus, “how the IRS will interpret each element [of an incentive agreement] from an enforcement perspective” remains murky, says Mike Kolodner, leader of the global renewable energy and U.S. power practice for Marsh McLennan risk-management consultants. “There is risk in each project. At the margin will be projects that probably will get audited and may or may not have clawbacks associated with tax credits they’ve taken.”

Debra McCormack, a lead consultant for Accenture, notes that “products may qualify for funding under the policies, but make certain you’re not going to get hit with penalties under the new regulations because you’re not following all of them.”

And while the CHIPS Act promises goodies for semiconductor fabricators making microchips in the United States, it also creates unprecedented constraints on them. “It’s going to limit significantly the ability for U.S companies to sell powerful chips to Saudi Arabia and China,” says Lior Susan, founder and managing partner of Eclipse, a venture-capital firm focusing on digital transformation of legacy industries. “Even if you don’t dip into the CHIPS Act, you’ll have those constraints.”

Faruki says private-equity outfits and the companies they own could be especially disadvantaged. “If you’re going to exit the deal in a couple of years but you’ve borrowed money from the government, that comes with strings,” he says. “Taking grant money will limit your decision and moves when you want to exit the deal.”

Help build an ecosoystem. The water is warm, so bring everybody in. “Help customers take advantage of funding” too, McCormack says. “Then secure their spend and make sure they purchase your widgets.”

Also, company leaders should be using their connections to forge partnerships across supply chains and even entire industries to best take advantage of new industrial policy. For example, seven car companies recently created a joint venture for an electric-car charging network aimed at snagging funds from the infrastructure bill passed in 2021.

Companies also can engage regional and local economic-development agencies “to help channel their activities and help the government in its quest to develop regional innovation ecosystems” under the new industrial policy, says Arun Gupta, CEO of NobleReach, a not-for-profit organization that seeks to develop tech talent. “Partnering with universities, local organizations and capital providers can help align their business models and bolster the value chain.”

Expect ulterior agendas. Some aspects of the new industrial policy are unapologetically stalking horses for White House priorities and “are less focused on economic growth, job creation and inflation reduction,” Wolf says.

Indeed, Sullivan says the administration’s industrial-policy philosophy includes a “global labor strategy that advances workers’ rights.” After Congress passed the CHIPS Act, for instance, Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo announced her department had enhanced requirements for any company seeking to obtain more than $150 million of the $39 billion in aid provided: They need to submit an employee childcare plan “in tandem with community stakeholders,” which CEOs could interpret as code for unions and progressive groups.

Play for the long term. What if the lineup changes in Washington? The long-term commitments required for many of the new projects should foreclose an about-face even if the American electorate overturns the status quo in 2024. Also, the social urgency in favor of environmental mitigation is only likely to accelerate.

“You’re going to have a hard time reversing the energy portion of industrial policy, because people are coming to the point of realization of what has to happen on the climate,” says George Sakellaris, CEO of Ameresco, which develops renewable-energy systems.

Thus, Susan warns, CEOs need to commit heavily right away and then stick with their plan for the long term to optimize industrial policy for their companies. “It’s not just a 12- to 18-month process,” he says.

0

1:00 - 5:00 pm

Over 70% of Executives Surveyed Agree: Many Strategic Planning Efforts Lack Systematic Approach Tips for Enhancing Your Strategic Planning Process

Executives expressed frustration with their current strategic planning process. Issues include:

Steve Rutan and Denise Harrison have put together an afternoon workshop that will provide the tools you need to address these concerns. They have worked with hundreds of executives to develop a systematic approach that will enable your team to make better decisions during strategic planning. Steve and Denise will walk you through exercises for prioritizing your lists and steps that will reset and reinvigorate your process. This will be a hands-on workshop that will enable you to think about your business as you use the tools that are being presented. If you are ready for a Strategic Planning tune-up, select this workshop in your registration form. The additional fee of $695 will be added to your total.

2:00 - 5:00 pm

Female leaders face the same issues all leaders do, but they often face additional challenges too. In this peer session, we will facilitate a discussion of best practices and how to overcome common barriers to help women leaders be more effective within and outside their organizations.

Limited space available.

10:30 - 5:00 pm

General’s Retreat at Hermitage Golf Course

Sponsored by UBS

General’s Retreat, built in 1986 with architect Gary Roger Baird, has been voted the “Best Golf Course in Nashville” and is a “must play” when visiting the Nashville, Tennessee area. With the beautiful setting along the Cumberland River, golfers of all capabilities will thoroughly enjoy the golf, scenery and hospitality.

The golf outing fee includes transportation to and from the hotel, greens/cart fees, use of practice facilities, and boxed lunch. The bus will leave the hotel at 10:30 am for a noon shotgun start and return to the hotel after the cocktail reception following the completion of the round.